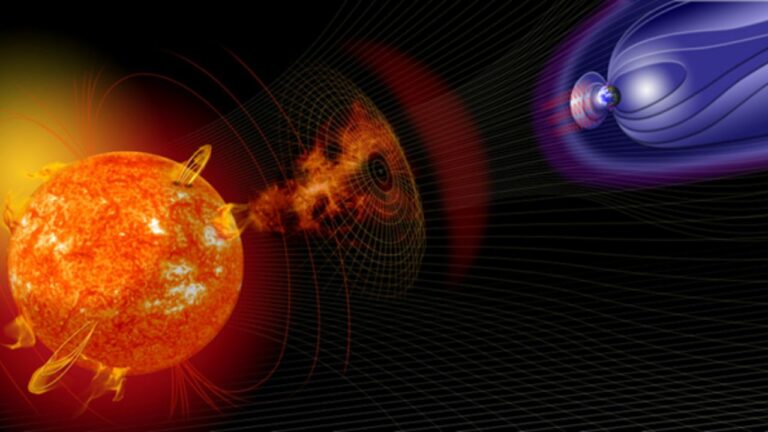

The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Solar Orbiter mission has revealed how the Sun acts as a giant particle accelerator, propelling electrons to near-light speeds and streaming them through the Solar System. These high-energy particles, known as Solar Energetic Electrons (SEEs), are now better understood thanks to the most comprehensive study of their origins to date.

Researchers found that SEE events fall into two clear categories: those triggered by explosive solar flares and those linked to massive plasma eruptions called coronal mass ejections (CMEs). Flares produce short, sharp bursts of particles, while CMEs generate a more gradual, sustained release of energetic electrons.

“By observing hundreds of events from close range, Solar Orbiter has given us the first clear evidence of these two distinct groups,” explained lead author Alexander Warmuth of the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam, Germany.

Between November 2020 and December 2022, the spacecraft recorded more than 300 SEE events using eight of its ten instruments. This unique vantage point allowed scientists to trace electrons back to their source on the Sun and study how they behave as they travel through space. Importantly, the data revealed why energetic particles sometimes appear to be delayed after a flare or CME—turbulence in the solar wind scatters and redirects them, creating a lag before detection.

The findings have critical implications for space weather forecasting. While both types of SEE events are significant, those associated with CMEs pose the greatest risk to satellites, astronauts, and spacecraft due to their higher particle intensity. By distinguishing between the two, scientists can now better predict and prepare for hazardous solar storms.

“Solar Orbiter is giving us the clearest picture yet of how particles travel from the Sun into the Solar System,” said ESA project scientist Daniel Müller. “This knowledge will help safeguard future missions and space infrastructure.”

Looking ahead, ESA plans to strengthen space weather monitoring with new missions. The Vigil spacecraft, set for launch in 2031, will provide a side view of the Sun to detect solar eruptions before they are visible from Earth. Meanwhile, the Smile mission, launching in 2026, will study how Earth’s magnetic shield responds to the solar wind and particle bursts.

Together, these missions promise to deepen our understanding of the Sun’s influence on our cosmic environment and help protect both technology and human explorers venturing deeper into space.